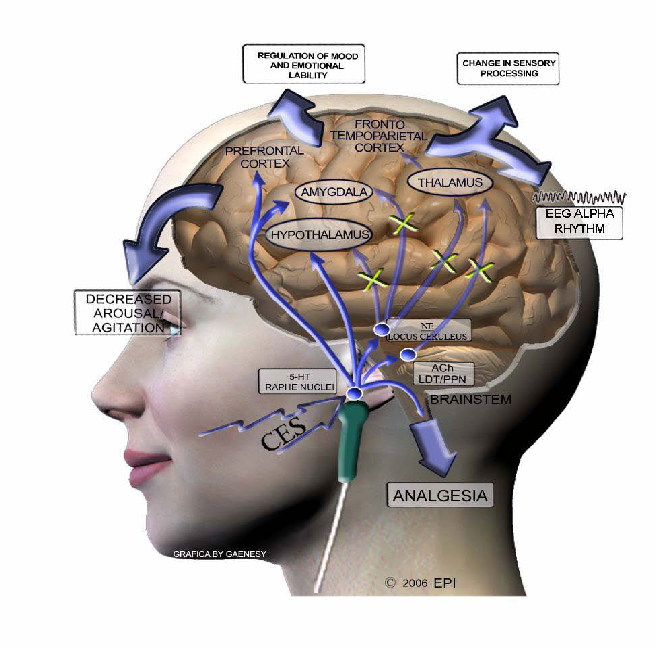

Neurofeedback therapy has gained traction as a non-invasive technique designed to enhance mental well-being and cognitive performance. Through the application of various modalities, including cranial electrotherapy stimulation (CES), practitioners target specific points on the head to alter brainwave activity. Understanding the intricacies of these techniques prompts a deeper examination of their physiological and psychological effects, ultimately inviting a playful challenge to conventional wisdom surrounding mental health treatments.

In the realm of neurofeedback, the head serves as both a canvas and a battleground for therapeutic intervention. The brain, with its intricate network of neurons, communicates through electrical impulses, creating a dynamic landscape of electrical activity indicative of one’s mental state. Techniques such as CES aim to harness this activity, propelling individuals towards desired states of relaxation, focus, and emotional regulation. To appreciate the efficacy of neurofeedback therapy thoroughly, one must delve into the various points on the head that practitioners utilize, fostering questions about their broader implications for health and wellbeing.

The following sections will dissect the neuroanatomy relevant to neurofeedback therapy, scrutinize the most common cranial points utilized in practice, and reflect on the societal perceptions surrounding mental health interventions.

Neuroanatomical Underpinnings of Neurofeedback Therapy

To comprehend neurofeedback therapy fully, a certain familiarity with neuroanatomy is indispensable. Understanding how the brain operates offers insight into how specific areas can be impacted through targeted interventions.

The brain can be broadly divided into distinct regions, each responsible for different functions. The frontal lobe, for instance, plays a crucial role in executive functions such as decision-making and impulse control. Herein lies the significance of targeting the prefrontal cortex during neurofeedback sessions. Altering alpha and beta wave activity in this area can enhance focus and cognitive flexibility, inviting the participant to engage in complex problem-solving tasks more effectively.

Shifting towards the occipital lobe, we discover its role in visual processing and its fascinating interplay with emotional responses. Recent studies have indicated that the occipital lobe’s electrical activity can be modulated to alleviate symptoms of anxiety and depression. Neurofeedback practitioners utilize electrodes placed at the back of the head to modulate these brainwave patterns, revealing an intriguing aspect of neuroplasticity. This capability to alter brain function signifies the potential for profound behavioral shift, prompting questions about autonomy over mental wellbeing.

The temporal lobes, positioned laterally in the brain, are instrumental in memory, emotion, and language comprehension. Given their multifaceted roles, these regions are frequently included in neurofeedback therapy, particularly when addressing issues like post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) or other trauma-related conditions. This leads to a critical inquiry: How do alterations in temporal lobe activity influence not just individual cognition, but also our broader understanding of traumatic experiences and their processing?

Common Points of Application in Neurofeedback Therapy

Practitioners of neurofeedback therapy employ a variety of cranial points to serve specific therapeutic purposes. Understanding these points opens up avenues for inquiry into the efficacy and suitability of various treatments for differing conditions.

The zygomatic process, located near the temples, is often manipulated during sessions aimed at relaxation. By influencing beta wave production in this region, practitioners can evoke a sense of calm, providing respite for those grappling with stress or anxiety. The intriguing interplay of the zygomatic process with emotional states invites a deeper exploration into the efficacy of localized interventions as opposed to more generalized therapeutic protocols.

Another crucial region is the parietal lobe, where the integration of sensory information occurs. By placing electrodes on the scalp over this area, clinicians can enhance attentional networks, thereby increasing individuals’ capacity to concentrate. The implications here are extensive and provoke critical thought: what does it mean to improve attention through electrical modulation? Can we balance cognitive enhancement with ethical considerations surrounding self-regulation and information consumption in an increasingly distracting world?

The midline of the scalp, often referred to in clinical practice as the “Cz” point, serves as a strategic focal point for many neurofeedback applications. Through this central location, practitioners can access and modify various brainwave frequencies, promoting increased self-awareness and emotional regulation. Engaging with the question of what constitutes self-awareness could create fruitful dialogues about the nature of identity and agency in mental health practices.

Moreover, the exponential growth of wearable technologies capable of monitoring brainwave activity has led to the democratization of neurofeedback methods. As individuals take the reins of their mental well-being, one must ponder the broader implications for society: is there a risk of self-coercive practices emerging in the pursuit of optimal cognitive performance? Are we embarking on a path where mental health becomes a competitive arena, rather than a collective endeavor centered on compassion and community?

Societal Perceptions and the Future of Neurofeedback Therapy

While the scientific and theoretical underpinnings of neurofeedback therapy are vital, societal perceptions play a crucial role in shaping the landscape of mental health interventions. Despite advancements, neurofeedback often encounters skepticism, primarily rooted in misunderstandings of its mechanisms and efficacy.

Part of this skepticism can be traced back to the stigma surrounding mental health treatments. The notion that one must “fix” their mental state through an external device can evoke discomfort and resistance. This invites a playful consideration: how can we more effectively communicate the benefits of neurofeedback therapy in a manner that resonates with diverse audiences? Perhaps a focus on empowerment rather than remediation can shift the narrative from one of illness to one of enhancement.

Furthermore, as researchers continue to elucidate the benefits of neurofeedback therapy, it is essential to advocate for rigorous clinical trials and studies supporting its use. The call for transparency is paramount—how can practitioners justify their methods without robust empirical support? The examination of this issue opens a broader dialogue about the responsibilities of mental health practitioners in enacting ethical guidelines that prioritize patient welfare.

Given the rise of technology and its ubiquity in daily life, one must also scrutinize how these innovations can be integrated responsibly into mental health practices. The interplay between neurofeedback and technology presents a tantalizing challenge: how do we leverage technological advancements while fostering authentic human connection and empathy in therapeutic settings?

In conclusion, neurofeedback therapy represents a fascinating convergence of neuroscience, technology, and psychological healing. By engaging with the cranial points utilized in therapy, one can uncover profound insights into the capacities of the human brain and its relationship with mental health. The playful challenge lies in questioning the precepts of traditional psychological interventions and inviting forward-thinking discussions that reincorporate humanity into the technological landscape of mental health care. Achieving balance through this intricate dialogue may indeed lead to a brighter future for mental well-being and cognitive enhancement.